Why is ‘faith’ (pistis, fides in the languages that dominate the classical world) so important to Christians? What did they mean by it and how did they practise it in early churches? Is Christian faith fundamentally different from divine-human pistis/fides in Greek and Roman religions or ancient Judaism, or essentially similar? And how (if at all) did Christian faith affect the practice of pistis and fides in Greek and Roman public life after Christianity became the state cult of the Roman empire?

Modern understandings of faith depend heavily on Augustine of Hippo, who defines it (De trin. 13.2.5) as fides quae and fides qua, belief in the body of Christian doctrine and the faith which takes place in the heart and mind of the believer. In 2015 I published Roman Faith and Christian Faith, which argues that the earliest Christians understood pistis/fides very differently. Faith was a relationship of trust and faithfulness between God and human beings, which also shaped relationships between human beings, the authority structure of churches, and the way Christians imagined the kingdom of heaven. Christians were unique in putting trust at the heart of their relationship with God and Christ, but their understanding and practice of pistis/fides were continuous with those of contemporary Greeks, Romans and Jews.

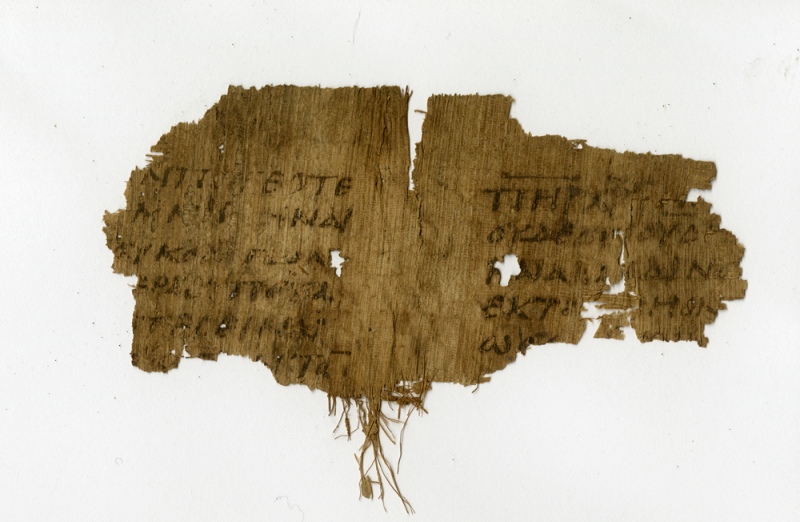

P.Oxy. 2067: fragment of a fifth-century papyrus codex containing the Nicene Creed. Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society. Photographer: Daniela Colomo.

The Invention of Faith, aims to show how Christian faith evolved in its first four centuries into the radically distinctive concept and practice familiar today. Many factors – social, political, theological and spiritual – shaped its development. Christians in different regions, for example, or who trace their genealogies back to different apostles, may describe it in slightly different ways. Groups within churches are increasingly instructed to express their faith in role-specific ways (householders by being loyal to their bishops; wives by obeying their husbands). In diverse contexts – the necropolis, the bishops’ council, the catechumens’ school – faith could be presented variously as a way of life, a rule, or a story. Certain aspects of it, notably that of propositional belief, were sharpened by both internal rivalries and external persecution. From the fourth century faith was powerfully affected by its new physical environment. Cyril of Jerusalem and Egeria the pilgrim, for instance, write of the great, new, richly decorated places of worship, scented with incense and mysterious with screens and smoke, as inflaming the hearts of the faithful with new passion for God.

Christian faith gained much greater significance when the later Roman empire adopted Christianity as its state cult. The final part of The Invention of Faith explores some of the ways in which Christian pistis/fides influenced later Roman government, law, social relations and religiosity. It seeks to show how, as the empire gave way to its successor states Christian faith played a central part in the evolution of near-eastern and western societies and mentalities in a formative period.

Researcher: Professor Teresa Morgan